CULTURAL PROPERTIES

PHOTO GALLERY

BUILDINGS

A mieidō is a hall built to house the image of a temple’s founder. At Senjuji Temple, the Mieidō enshrines a wooden statue of Shinran Shōnin (1173–1263), the founder of both Jōdō Shinshū Buddhism and Senjuji. Portraits of later abbots hang on either side of Shinran’s statue.

The Mieidō is designed to represent Jōdō Shinshū cosmology through its architecture. Just inside the entrance, the hall is plain and unadorned, but the back wall is covered with gold leaf and brightly colored paintings. The inner altar is also covered in gold leaf and represents Gokuraku—the Pure Land of Amida Nyorai, who is the Buddha of Infinite Light and Life. Flowers are believed to fall from the sky in the Pure Land, and the panels of the coffered ceiling are painted with chrysanthemums.

The plaque on the transom above the altar reads kenshin, a Buddhist term meaning "to discover truth through wisdom." It is also the first half of Shinran’s posthumous name, Kenshin Daishi. The transoms are covered in geometric designs painted blue, green, and red. Carvings of birds and red and white peonies grace each section of the upper transom, and the lower transoms are decorated with carvings of enormous peonies covered in gold leaf. Lotus plants and flowers are a recurring motif on the walls of the hall and symbolize a person’s potential to enter the Pure Land. Just as the lotus plant rises from muddy waters, so too can people rise towards the Pure Land from the defilement of the mundane world.

The original Mieidō was completed in the 1400s, but it was destroyed in a fire in 1645. Reconstruction began in 1666 and was completed in 1679, making the Mieidō the oldest building at Senjuji. The original hall faced south, but during the 1600s most Jōdō Shinshū temples were built facing the east, to better represent the location of the Pure Land in the west. There was significant discussion regarding whether to change the orientation of the hall, but in the end, the Mieidō was rebuilt facing south. Practical reasons—like the fact that a pilgrimage road to Ise runs along the southern border of the temple, and that the temple’s lanterns and candles would be blown out by the strong northeastern winds of spring and summer—won out.

Many of the carpenters and craftsmen that built the new Mieidō were employed by the Tokugawa shogunate. Most were based in the Kantō region, and many had worked on the halls at Nikkō in Tochigi Prefecture. The Mieidō is built in a traditional Japanese style, and has a tall, hip-and-gable roof with detailed carvings decorating the space under the gables.

The Mieidō is the largest building at Senjuji, covering over 1,400 square meters or 780 tatami mats. It was designed as a hall for large gatherings and is still used for sermons and other services. Services are held in the Mieidō daily at 7 a.m..

The Nyoraidō is the primary worship hall of Senjuji and houses the main object of worship, a statue of Amida Nyorai from which it gets its name. Amida Nyorai is also known as the Buddha of Infinite Light and Life and is the principle deity of Jōdō Shinshū Buddhism. Believers chant the nenbutsu, "Hail the Buddha of Infinite Light (namu-amida-butsu)," which expresses both belief in and gratitude to Amida Nyorai.

Unlike the Mieidō, the Nyoraidō is built in a Zen architectural style and is about half the size. However, it is just as tall as the Mieidō. The Nyoraidō’s architectural features indicate its importance as the main hall of Senjuji. The curved gable over the entrance and the pent roof that skirts the middle of the structure were difficult and costly to build in the eighteenth century, when the hall was constructed. Underneath the eaves of the hip-and-gable roof are detailed carvings. For example, the cranes under the east and west gables of the Nyoraidō are so lifelike that they are said to have just taken flight after visiting the pond behind the Nyoraidō.

The large, tiled roof is quite heavy, and the upper roof is supported in part by an assembly of layered brackets between the two roofs. The ends of these brackets are carved into the shape of dragons. The mouths of the dragons alternate—open and closed. This is an expression of the first and last sounds of the Japanese syllabary, "ah" and "un," representing the beginning and end of all things. In addition to dragons, elephants (spiritually significant in Buddhism) and baku (mythical animals that are thought to eat metal, thus preventing war) have been carved into the brackets.

The principal object of worship is a standing wooden sculpture of Amida Nyorai covered in gold leaf. It is the work of Kaikei (dates unknown), a leading artist of the Kei school of Buddhist sculpture who was active around the turn of the thirteenth century. On transoms above the image of Amida are three panels depicting swirling gold clouds. Floating and flying between the clouds are birds and numerous musical instruments including a flute, taiko drum, and conch shell. On the transoms running perpendicular to the altar are detailed carvings of animals, such as a monkey, rabbit, horse, and tiger.

Construction of the Nyoraidō took about thirty years in total, due in large part to the time it took to raise enough money to complete the project. Building began in 1719 and continued steadily for six years before stalling due to a lack of funds. Work began again in 1740, and the hall was finally completed in 1748. In contrast to the Mieidō, the Nyoraidō was built by local craftsmen and financed by lay people. The temple still has all the records of the construction process, from initial plans to the purchase of the materials, as well as a complete list of donors and their contributions.

A sanmon gate is the main entrance to the temple and marks the separation of sacred temple grounds from the profane world outside. The enclosed upper level of Senjuji’s sanmon contains a space for worship, and images of Shakyamuni (the historical Buddha) and two attendants are enshrined there.

The sanmon at Senjuji is built in the most formal style for such gates, complementing the Mieidō directly across the courtyard. The gate structure is held up by 5 rows of 6 pillars, creating five open bays. A "bay" refers to the width between the main columns, a space of slightly less than 2 meters. The three bays in the middle of the gate each have a set of thick, wooden double doors.

The lower level of the sanmon supports the upper portion with bracket arms inserted through the main pillars, rather than a bearing block on top of the pillars. It is similar to the sanmon at Tōfukuji Temple in Kyoto (built in 1425), but the extension of the eaves over the three central bays on the interior side of the gate is unique to Senjuji.

Construction began on the gate in 1693 and was finished in 1704. These dates are known from inscriptions on roof tiles discovered during a three-year-long renovation that began in 1993. The gate is 20 meters across, 9 meters deep, and 15.5 meters high.

The Karamon Gate is directly opposite the Nyoraidō and matches the hall’s architectural style. Its name comes from the curved gables called karahafu on the front and rear sides of the gate. During the Edo period (1603–1867), karamon gates were generally reserved for the exclusive use of daimyo, imperial envoys, and other high-ranking individuals. Now this gate is open to the public.

Everything about Karamon Gate is meant to convey prestige. It is made entirely of carefully selected, high-quality zelkova wood. The roof is thatched with slats made of Japanese cypress, and intricate carvings fill almost every available surface.

The carvings depict animals, flowers, and figures from the Japanese classics. The most prominent carvings are Chinese lions at play among peonies. The lions have glass eyes, and the whites of their eyes is striking against the dark wood.

Chrysanthemums and trailing vines also feature prominently on the doors, transoms, and under the gables. Smaller figures in the gate include sumo wrestlers who appear to be holding up the roof.

It took 35 years to build the gate. The lumber was milled in 1809, groundwork began in 1820, and the ridge-raising ceremony was finally held in 1844. The gate was renovated in 2010.

The three-story tower on top of this gate houses a large taiko drum. On either side of the gate are rooms that were used for storage and by the gatekeepers on watch. The drum in the tower was used by the gatekeepers to sound the time, much like a church bell in medieval Europe.

Before Japan adopted Western timekeeping practices in 1872, Japanese people used temporal hours. Daytime and nighttime were each divided into 6 hours, which varied in length with the seasons. Every hour, the drum keeper would climb up into the tower and strike the drum to notify the temple monks and townsfolk of the time.

Although no one knows exactly when this tower was built or first used for timekeeping, records show that it was in use as early as 1712. An illustration from 1762 shows the gate with a single-story tower, and there are records from 1861 that include a proposal to increase the turret to three levels. It is rare for a drum tower such as this to be three stories tall.

The tower is still used, but only once a year. A drum is sounded one hour before the Hōonkō, the annual memorial observance for Shinran on the anniversary of his death. Although the original taiko drum has been replaced with a new one, the old timekeeping drum has been preserved. According to inscriptions inside the drum, it was made in 1729 and has been repaired three times. It is a valuable keepsake of the temple.

The mausoleum of Shinran Shōnin (1173–1263) is located to the west of the Nyoraidō. Shinran was the founder of Jōdō Shinshū Buddhism. Shinran’s physical remains are interred across a number of Jōdō Shinshū temples in Japan—five of his teeth are interred at Senjuji.

The Gobyō Haidō is a hall within the grounds of the mausoleum and is used for memorial services. The small building has a large, ornate roof, and its exterior is lavishly decorated with elaborate carvings of birds and flowers. In contrast the interior is plain and unadorned.

The roof has a curved gable (karahafu) over the entrance, and above that, as well as on the rear of the building, are steeply pointed triangular gables. Under all the gables are carvings of birds in pine trees and bamboo thickets, along with chrysanthemums, lotus flowers, and peonies. Chrysanthemums feature prominently in the roof tiles and metalwork. At the top of the karahafu is a metal sculpture of a peacock.

Shinran passed away on January 16, 1262, and the monks visit the Haidō on the sixteenth of every month as part of the memorial ceremony for Shinran.

The mausoleum of Shinran Shōnin (1173–1263) is surrounded by a latticed fence. The fence has two gates: an ornate formal gate on the south side and a simple gate on the east side. Both the formal gate and the fence are roofed with Japanese cypress (hinoki). The gate has curved gables on both sides, with the entrance on the long, straight side. The gate entrance is about 1.5 meters wide and is shut with a set of double doors.

The fence is made up of 27 sections of wood latticework set between posts and covered with a pitched roof. This type of fence is called a mizugaki and is commonly used as the boundary marker enclosing the most sacred part of a temple or shrine. Along with the intricate latticework are inlaid carvings of narcissus, lotus flowers, horsetail, and dandelions. These carvings are based on the design of Yamamoto Baiitsu (1783–1856), a master of bird-and-flower painting (kachōga).

The formal gate on the south side of the enclosure opens onto the Haidō. Beyond the Haidō is a raised, rectangular burial mound where Shinran’s remains are buried. Surrounding the mound are the graves of the abbots of Senjuji. According to temple records, the mausoleum dates to 1672. The gate and the fence were built in 1858 and were most recently restored between 2010 and 2012.

The Tsūten Bridge is an elevated corridor that connects the Mieidō and the Nyoraidō. Built in 1802, it is nearly 32 meters in length and, like the Karamon Gate, is made of zelkova wood. The bridge is completely open on the sides and lit by golden lanterns engraved with the names of the people who donated them.

The tiled roof gently curves from the center ridge to the eaves in a style called terimukuri, with a curved gable at each end. The gable echoes the shape of the Karamon Gate and the entrance to the Nyoraidō. These curved portions are notoriously difficult to create and indicate the wealth and prestige of the temple during the Edo period (1603–1867).

The bridge and the Nyoraidō were restored during the 1980s; the bridge was completely disassembled and put back together, and any broken or rotting components were carefully cut out and replaced.

The bell tower at Senjuji is a typical Japanese Buddhist design. It is square, and 12 pillars support a heavy hip-and-gable roof. Visually it resembles the bell tower at Tōdaiji Temple in Nara, but there is no evidence of any connection during the bell tower’s construction. The tower is believed to have been completed in 1713 based on an inscription found on one of the roof tiles during a major restoration in 1993.

The temple bell was lost in the 1645 fire that devastated most of Senjuji. A new bell was cast in 1652, on the sixth anniversary of the death of Gyōchō Shōnin (1614–1646), fifteenth abbot of the temple. Gyōchō died in an act of self-sacrifice to protect the temple’s most valuable treasures. Gyōchō went to Edo (now Tokyo) to report having assumed his father’s position as head abbot of Senjuji. However, he was heavily criticized for receiving such a promotion without the permission of the shogunate. The daimyo of the Tsu domain tried to smooth things over, but the shogunate stipulated that documents written by the temple’s founder, Shinran Shōnin (1173–1263), would have to be turned over to the shogunate. To refuse was a matter of death, and Gyōchō committed seppuku in Edo at the age of 32 rather than hand over the most prized possession of the temple.

Creation of the new bell was sponsored by Gyōchō’s wife, the eldest daughter of the first daimyo of the Tsu domain, who hoped that the sound of the bell would carry her husband’s memory in every direction. She commissioned the bell from Tsuji Echigo no Kami Shigetane (dates unknown), a master craftsman from Tsu domain.

The bell is rung every morning at 6:30 and before services in the Mieidō.

The Shishunkan is a reception hall built in 1878 to receive important guests visiting Senjuji. Today, the hall is used in appointment ceremonies for new abbots. The name is celebratory and means "the pleasures of spring (or youth)."

The Meiji Emperor (1852–1912) stayed in the Shishunkan when he visited Senjuji in July of 1880. He slept in a small room to the east of the main room. The rings used for securing mosquito netting over his futon during his visit are still affixed to the walls. To the west of the main room is a toilet, and an interior corridor runs around the perimeter of the hall.

The main room of the hall contains a toko no ma, a decorative alcove usually adorned with an artistic scroll or flower arrangement. The toko no ma is covered in gold leaf, and the rest of the room’s decorations also use gold liberally. The designs on the sliding fusuma doors are relatively simple in the outermost section of the room, becoming more intricate and lavish towards the interior of the hall. In the innermost area, the doors and ceiling are completely covered with gold. This space, the kami no ma, was used for audiences with the emperor during his visit.

The Shishunkan is not open to the public.

The Otaimensho is a hall for encounters between the abbot of Senjuji and the lay community. It was used regularly for such meetings until the early twentieth century, but these events are now held only once a year. It has also been used for tea gatherings and as a set for films. The original building was destroyed by fire in 1783, but it was rebuilt in 1786.

The large hall can be partitioned into smaller rooms using sliding doors. The rooms are arranged in three rows of five rooms each. The further back in the hall, the more prestigious. The focal point and highest-ranking area of the three main sections is the center-back room, which has a raised wooden floor and a large painting of a pair of red-crowned cranes under a snowy pine. The innermost room on the west side of the hall contains a Buddhist altar where a thirteenth-century statue of Amida Nyorai is enshrined. The room at the far end of the east side is not an exalted space; rather it is a private room for the head abbot of Senjuji to use before stepping into the room in front of the painting of the cranes and pine tree. Its sliding panels are usually closed.

The Otaimensho is connected to surrounding buildings by a covered passage. It has a tiled, hip-and-gable roof with a curved gable over the entrance.

The Otaimensho is not open to the public.

This building is used for receiving high-ranking visitors to the temple. The large, curved gable over the entrance indicates the prestige of the building and that the entrance is used for special guests.

The Ōgenkan and Otaimensho burned down in 1783, and the Ōgenkan was rebuilt in 1790. At the time it was located east of the Otaimensho and faced east. In 1878, it was moved to its present location, west of the Otaimensho, and reoriented so that it faces south. It is directly in front of the Shishunkan, and the move is thought to have some connection with the preparations for the visit of the Meiji Emperor (1852–1912) in 1880.

Just inside the sanmon gate is the Chajo, literally "a place for tea." The building was used as a communal rest area by the lay people who take care of the temple grounds. The style of the building is similar to the other buildings of Senjuji, with a large, curved gable over the entrance to the building. Through the arched entrance is a large butsudan altar and worship area. The interior of the Chajo was refurbished in 2018 and contains a spacious area with both tables and chairs and low tables for sitting directly on the tatami mats. The public is encouraged to use this space.

The opposite side of the building was the tea preparation area and contains the original tea hearth with two enormous built-in kettles. One of the kettles is inscribed with the year 1760. Both the hearth and the entire building are thought to have been built in that year. Tea was made in the large kettles and served to people attending religious services at Senjuji until the 1970s.

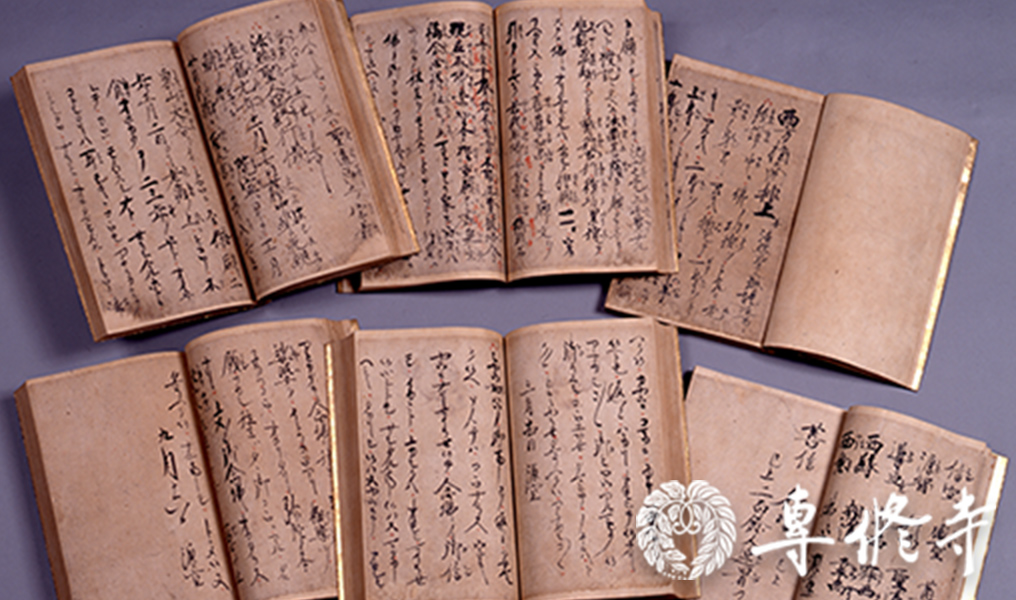

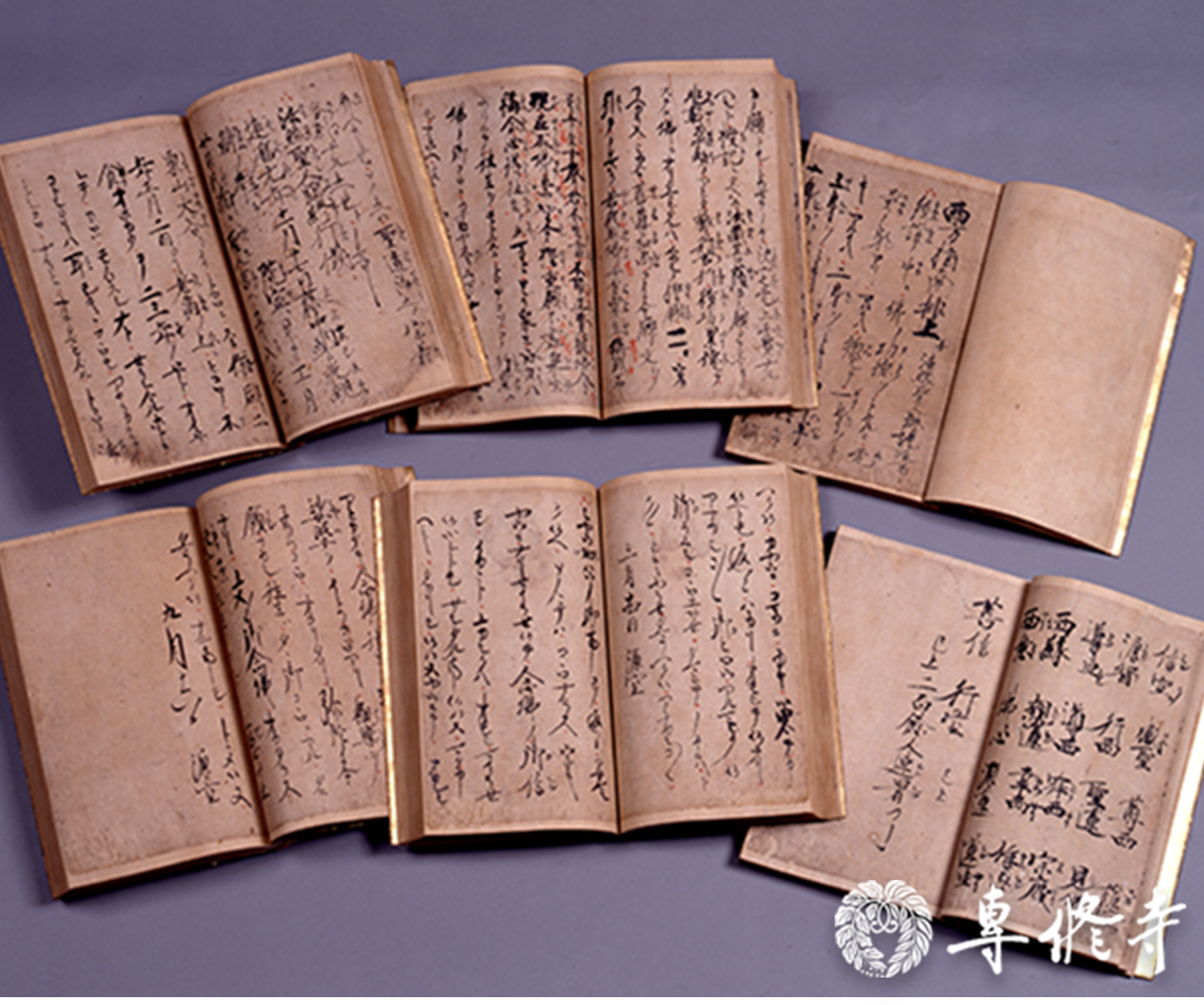

This collection of letters, sermons, and reports on the activities of Hōnen (1133–1212) is commonly translated as "Notes on Guidance Toward Birth in the West" in English.

Hōnen was the founder of Pure Land Buddhism (Jōdō Shū) and the teacher of Shinran (1173–1263). The works were written down by Shinran and are based on his recollections and experiences with Hōnen. According to postscripts at the back of each work, Shinran completed the texts at the age of 84, between October 1256 and the following New Year. They are the oldest records of Hōnen’s activities and are considered the best example of Shinran’s later writings. The texts have been bound into six books and are divided into three volumes.

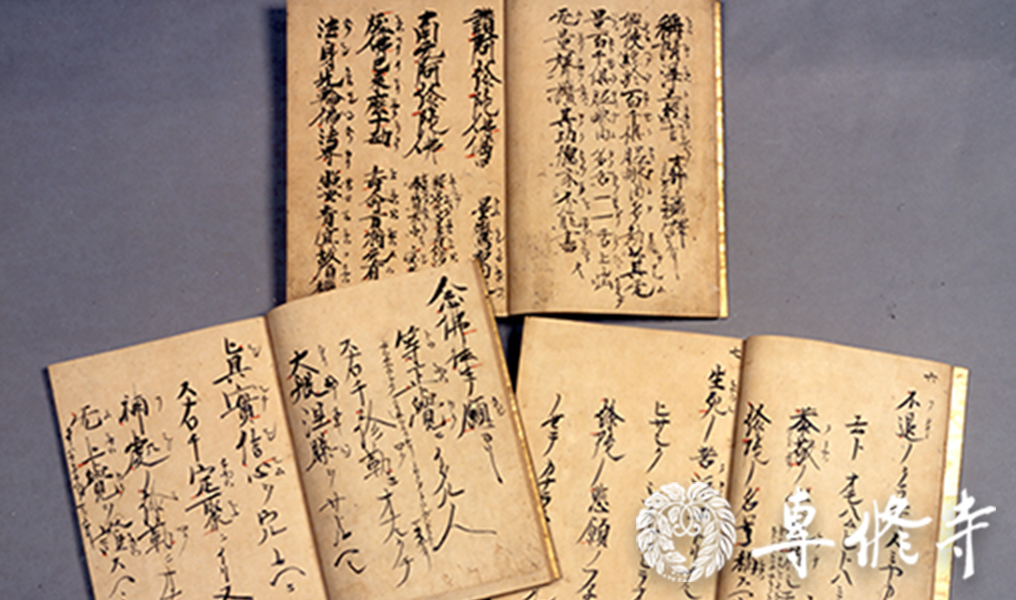

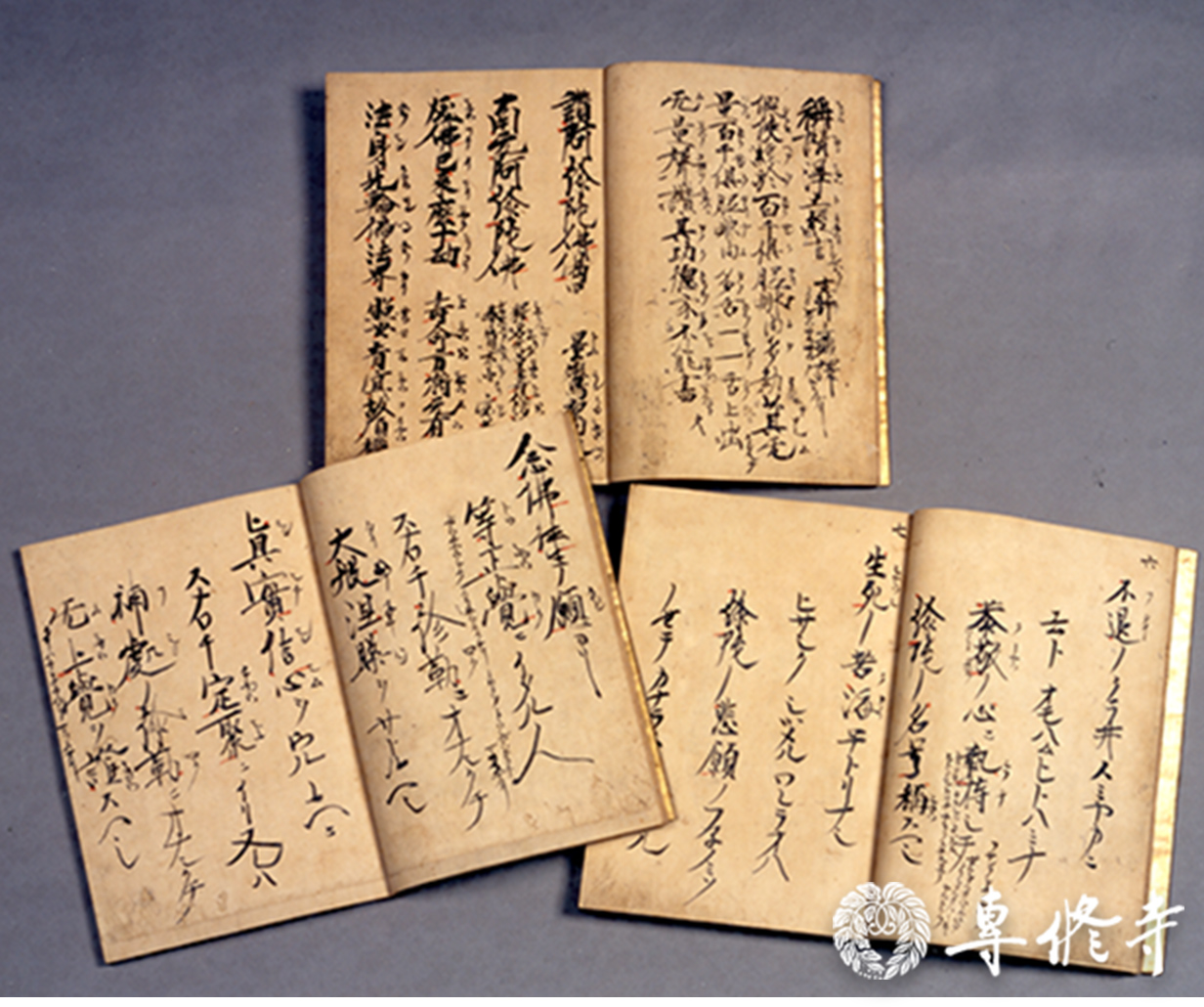

The Sanjō Wasan, literally the "three books of Japanese Buddhist Hymns," were written by Shinran in the middle of the thirteenth century. The three volumes include general verses of praise, tributes to historic masters of Buddhism, and verses regarding Buddhism throughout time. Each entry is quite brief, and they are still sung today. For example, the following verse describes Amida Nyorai, the Buddha of Infinite Life and Light.。

he light is more luminous than the heavenly bodies; Thus Amida is called "Light that Surpasses the Sun and Moon." Even Shakyamuni's praise cannot exhaust its virtues, So take refuge in the one without equal.

The Three Volumes

The Jōdo Wasan (Hymns of the Pure Land) consists of 118 verses and was written around 1248. The Kōso Wasan (Hymns of the Masters of the Pure Land), consists of 119 verses and is also thought to have been written around 1248. The Shōzōmappō Wasan (Hymns of the Dharma Ages) was written around 1257 and consists of 116 verses.

(Translation by Rev. George Gatenby; accessed on https://shinbuddhism.info/jw15.htm)